Setting up the game

Help players flesh out their characters before starting your own story setup. Ask them questions about their choices (example questions are included in the sheet) and help them answer questions if they are stuck. Brainstorm with players how they can use their bizarrely worded items or goals. Be creative in the interpretations of the words on the sheet, and ask other players to help come up with more ideas. Connect characters together if they have seemingly similar or opposite goals. For example, if two players are entrepreneurs, have they worked together for an eternity and how did that affect their relationship?

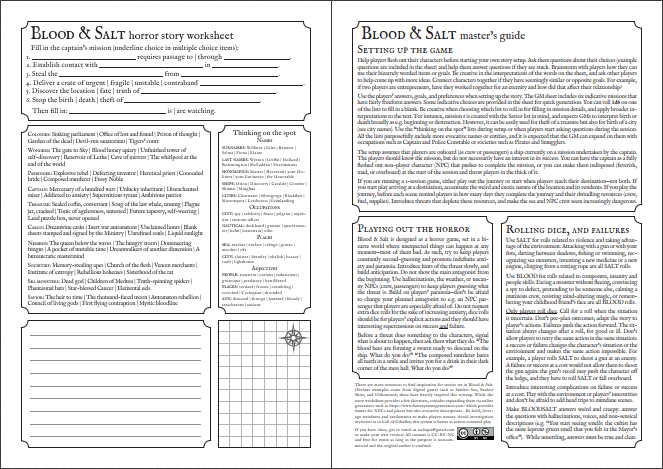

Use the players' answers, goals, and preferences when setting up the story. The GM sheet includes six indicative missions that have fairly freeform answers. Some indicative choices are provided in the sheet for quick generation. You can roll 1d6 on one of the lists to fill in a blank. Be creative when choosing which list to roll in for filling in mission details, and apply broader interpretations to the text. For instance, mission 6 is created with the Savior list in mind, and expects GMs to interpret birth or death broadly as e.g. beginning or destruction. However, it can be easily used for theft of a treasure but also for birth of a city (see city names). Use the "thinking on the spot" lists during setup or when players start asking questions during the session. All the lists purposefully include more evocative names or entities, and it is expected that the GM can expand on them with occupations such as Captain and Police Constable or societies such as Pirates and Smugglers.

The setup assumes that players are onboard (as crew or passengers) a ship currently on a mission undertaken by the captain. The players should know the mission, but do not necessarily have an interest in its success. You can have the captain as a fully fleshed out non-player character (NPC) that pushes to complete the mission, or you can make them indisposed (feverish, mad, or overboard) at the start of the session and throw players in the thick of it.

If you are running a 1-session game, either play out the journey or start when players reach their destination—not both. If you start play arriving at a destination, accentuate the weird and exotic nature of the location and its residents. If you play the journey, before each scene remind players in how many days they complete the journey and their dwindling resources (crew, fuel, supplies). Introduce threats that deplete these resources, and make the sea and NPC crew seem increasingly dangerous.

Playing out the horror

Blood & Salt is designed as a horror game, set in a bizarre world where unexpected things can happen at any moment—most of them bad. As such, try to keep players constantly second-guessing and promote indefinite anxiety and paranoia. Introduce hints of the threat slowly, and build anticipation. Do not show the main antagonist from the beginning. Use hallucinations, the weather, or uncanny NPCs (crew, passengers) to keep players guessing what the threat is. Build on players' paranoia—don't be afraid to change your planned antagonist to e.g. an NPC passenger that players are especially afraid of. Do not request extra dice rolls to increase tension; dice rolls should have interesting repercussions on success and failure. Use BLOODSALT rolls to help players along while creeping them out with hallucinations and nonsensical descriptions.

Before a threat does something to the characters, signal what is about to happen, then ask them what they do. "The blood bees start swarming over the ship. What do you do?" "With a toothy smile, the composed murderer invites you to their dark corner of the mess hall. What do you do?"

Rolling dice, and failures

Use SALT for combat and nautical skills, e.g. brawling, firing cannons, steering the ship in a storm, swimming.

Use BLOOD for rolls related to composure, insanity and people skills, e.g. facing a terrifying monster, calming the crew, impersonating someone, controlling or channeling magic, resisting hunger, holding your breath.

Only players roll dice. Call for a roll when the situation is uncertain. Don’t pre-plan outcomes; adapt the story to player’s actions. Failures push the action forward. The situation always changes after a roll, for good or ill. Don’t allow players to retry the same action in the same situation: a success or failure changes the character’s situation or the environment and makes the same action impossible. If a player rolls SALT to shoot a gun at an enemy, failure or success at a cost would not allow them to shoot the gun again: the gun’s recoil may push the character off the ledge, and they have to roll SALT or fall overboard.

Do not ask for rolls not related to BLOOD or SALT (e.g. sneaking about). If it’s an action, have it succeed but with a cost that pushes the action forward. Sneaking into the hold succeeds, but a sailor spots you on your way out: convince them with BLOOD or take them out with SALT. If you can’t think of something that moves the action forward, delay the cost until an appropriate time: bandaging a wound works fine short-term, until the wound opens at the heat of battle. Do not roll for knowledge: if the character has a skill or edge that would warrant that knowledge, they know it. A Doctor may know rumors of or have contacts at an insane asylum but not the local crime gang.